An expression is a language fragment that can be evaluated to return a value. For example, the expression 2 + 3 returns the value 5. Expressions are the building blocks from which queries are constructed. SQL++ supports nearly all of the kinds of expressions in SQL, and adds some new kinds as well.

SQL++ is an orthogonal language, which means that expressions can serve as operands of higher level expressions. By nesting expressions inside other expressions, complex queries can be built up. Any expression can be enclosed in parentheses to establish operator precedence.

In this section, we’ll discuss the various kinds of SQL++ expressions.

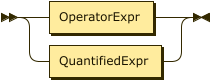

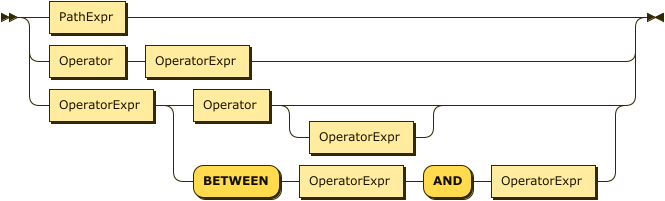

Operator Expressions

Operators perform a specific operation on the input values or expressions. The syntax of an operator expression is as follows:

OperatorExpr

The language provides a full set of operators that you can use within its statements. Here are the categories of operators:

-

Arithmetic Operators, to perform basic mathematical operations;

-

Collection Operators, to evaluate expressions on collections or objects;

-

Comparison Operators, to compare two expressions;

-

Logical Operators, to combine operators using Boolean logic.

The following table summarizes the precedence order (from higher to lower) of the major unary and binary operators:

| Operator | Operation |

|---|---|

EXISTS, NOT EXISTS |

Collection emptiness testing |

^ |

Exponentiation |

*, /, DIV, MOD (%) |

Multiplication, division, modulo |

+, - |

Addition, subtraction |

|| |

String concatenation |

IS NULL, IS NOT NULL, IS MISSING, IS NOT MISSING, |

Unknown value comparison |

BETWEEN, NOT BETWEEN |

Range comparison (inclusive on both sides) |

=, !=, <>, <, >, <=, >=, LIKE, NOT LIKE, IN, NOT IN, IS DISTINCT FROM, IS NOT DISTINCT FROM |

Comparison |

NOT |

Logical negation |

AND |

Conjunction |

OR |

Disjunction |

In general, if any operand evaluates to a MISSING value, the enclosing operator will return MISSING;

if none of the operands evaluates to a MISSING value but there is an operand which evaluates to a NULL value,

the enclosing operator will return NULL. However, there are a few exceptions listed in

comparison operators and logical operators.

Arithmetic Operators

Arithmetic operators are used to exponentiate, add, subtract, multiply, and divide numeric values, or concatenate string values.

| Operator | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

+, - |

As unary operators, they denote a |

SELECT VALUE -1; |

+, - |

As binary operators, they add or subtract |

SELECT VALUE 1 + 2; |

* |

Multiply |

SELECT VALUE 4 * 2; |

/ |

Divide (returns a value of type |

SELECT VALUE 5 / 2; |

DIV |

Divide (returns an integer value if both operands are integers) |

SELECT VALUE 5 DIV 2; |

MOD (%) |

Modulo |

SELECT VALUE 5 % 2; |

^ |

Exponentiation |

SELECT VALUE 2^3; |

|| |

String concatenation |

SELECT VALUE "ab"||"c"||"d"; |

Collection Operators

Collection operators are used for membership tests (IN, NOT IN) or empty collection tests (EXISTS, NOT EXISTS).

| Operator | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

IN |

Membership test |

FROM customers AS c |

NOT IN |

Non-membership test |

FROM customers AS c |

EXISTS |

Check whether a collection is not empty |

FROM orders AS o |

NOT EXISTS |

Check whether a collection is empty |

FROM orders AS o |

Comparison Operators

Comparison operators are used to compare values.

The comparison operators fall into one of two sub-categories: missing value comparisons and regular value comparisons. SQL++ (and JSON) has two ways of representing missing information in an object — the presence of the field with a NULL for its value (as in SQL), and the absence of the field (which JSON permits). For example, the first of the following objects represents Jack, whose friend is Jill. In the other examples, Jake is friendless à la SQL, with a friend field that is NULL, while Joe is friendless in a more natural (for JSON) way, i.e., by not having a friend field.

{"name": "Jack", "friend": "Jill"}

{"name": "Jake", "friend": NULL}

{"name": "Joe"}

The following table enumerates all of the comparison operators available in SQL++.

| Operator | Purpose | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

IS NULL |

Test if a value is NULL |

FROM customers AS c |

|

IS NOT NULL |

Test if a value is not NULL |

FROM customers AS c |

|

IS MISSING |

Test if a value is MISSING |

FROM customers AS c |

|

IS NOT MISSING |

Test if a value is not MISSING |

FROM customers AS c |

|

IS UNKNOWN |

Test if a value is NULL or MISSING |

FROM customers AS c |

|

IS NOT UNKNOWN |

Test if a value is neither NULL nor MISSING |

FROM customers AS c |

|

IS KNOWN (IS VALUED) |

Test if a value is neither NULL nor MISSING |

FROM customers AS c |

|

IS NOT KNOWN (IS NOT VALUED) |

Test if a value is NULL or MISSING |

FROM customers AS c |

|

BETWEEN |

Test if a value is between a start value and a end value. The comparison is inclusive of both the start and end values. |

FROM customers AS c WHERE c.rating BETWEEN 600 AND 700 SELECT *; |

|

= |

Equality test |

FROM customers AS c |

|

!= |

Inequality test |

FROM customers AS c |

|

<> |

Inequality test |

FROM customers AS c |

|

< |

Less than |

FROM customers AS c |

|

> |

Greater than |

FROM customers AS c |

|

<= |

Less than or equal to |

FROM customers AS c |

|

>= |

Greater than or equal to |

FROM customers AS c |

|

LIKE |

Test if the left side matches a pattern defined on the right side; in the pattern, "%" matches any string while "_" matches any character. |

FROM customers AS c WHERE c.name LIKE "%Dodge%" SELECT *; |

|

NOT LIKE |

Test if the left side does not match a pattern defined on the right side; in the pattern, "%" matches any string while "_" matches any character. |

FROM customers AS c WHERE c.name NOT LIKE "%Dodge%" SELECT *; |

|

IS DISTINCT FROM |

Inequality test that that treats NULL values as equal to each other and MISSING values as equal to each other |

FROM orders AS o |

|

IS NOT DISTINCT FROM |

Equality test that treats NULL values as equal to each other and MISSING values as equal to each other |

FROM orders AS o |

The following table summarizes how the missing value comparison operators work.

| Operator | Non-NULL/Non-MISSING value | NULL value | MISSING value |

|---|---|---|---|

IS NULL |

FALSE |

TRUE |

MISSING |

IS NOT NULL |

TRUE |

FALSE |

MISSING |

IS MISSING |

FALSE |

FALSE |

TRUE |

IS NOT MISSING |

TRUE |

TRUE |

FALSE |

IS UNKNOWN |

FALSE |

TRUE |

TRUE |

IS NOT UNKNOWN |

TRUE |

FALSE |

FALSE |

IS KNOWN (IS VALUED) |

TRUE |

FALSE |

FALSE |

IS NOT KNOWN (IS NOT VALUED) |

FALSE |

TRUE |

TRUE |

Logical Operators

Logical operators perform logical NOT, AND, and OR operations over Boolean values (TRUE and FALSE) plus NULL and MISSING.

| Operator | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

NOT |

Returns true if the following condition is false, otherwise returns false |

SELECT VALUE NOT 1 = 1; |

AND |

Returns true if both branches are true, otherwise returns false |

SELECT VALUE 1 = 2 AND 1 = 1; |

OR |

Returns true if one branch is true, otherwise returns false |

SELECT VALUE 1 = 2 OR 1 = 1; |

The following table is the truth table for AND and OR.

| A | B | A AND B | A OR B |

|---|---|---|---|

TRUE |

TRUE |

TRUE |

TRUE |

TRUE |

FALSE |

FALSE |

TRUE |

TRUE |

NULL |

NULL |

TRUE |

TRUE |

MISSING |

MISSING |

TRUE |

FALSE |

FALSE |

FALSE |

FALSE |

FALSE |

NULL |

FALSE |

NULL |

FALSE |

MISSING |

FALSE |

MISSING |

NULL |

NULL |

NULL |

NULL |

NULL |

MISSING |

MISSING |

NULL |

MISSING |

MISSING |

MISSING |

MISSING |

The following table demonstrates the results of NOT on all possible inputs.

| A | NOT A |

|---|---|

TRUE |

FALSE |

FALSE |

TRUE |

NULL |

NULL |

MISSING |

MISSING |

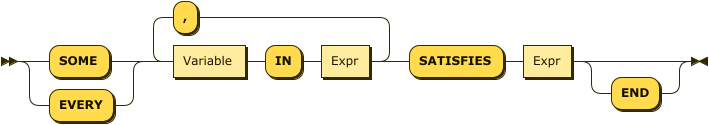

Quantified Expressions

QuantifiedExpr

Synonym for SOME: ANY

Quantified expressions are used for expressing existential or universal predicates involving the elements of a collection.

The following pair of examples illustrate the use of a quantified expression to test that every (or some) element in the

set [1, 2, 3] of integers is less than three. The first example yields FALSE and second example yields TRUE.

It is useful to note that if the set were instead the empty set, the first expression would yield TRUE ("every" value in an empty set satisfies the condition) while the second expression would yield FALSE (since there isn’t "some" value, as there are no values in the set, that satisfies the condition). To express a universal predicate that yields FALSE with the empty set, we would use the quantifier SOME AND EVERY in lieu of EVERY.

A quantified expression will return a NULL (or MISSING) if the first expression in it evaluates to NULL (or MISSING).

Otherwise, a type error will be raised if the first expression in a quantified expression does not return a collection.

EVERY x IN [ 1, 2, 3 ] SATISFIES x < 3 (1) SOME x IN [ 1, 2, 3 ] SATISFIES x < 3 (2)

| 1 | Returns FALSE |

| 2 | Returns TRUE |

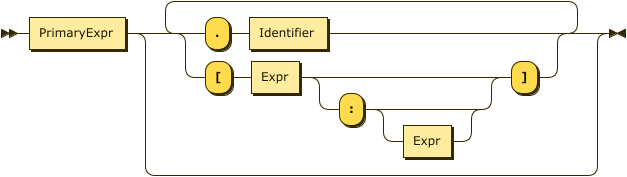

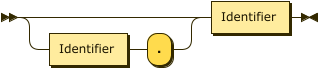

Path Expressions

PathExpr

Components of complex types in the data model are accessed via path expressions. Path access can be applied to the result of a query expression that yields an instance of a complex type, for example, an object or an array instance.

For objects, path access is based on field names, and it accesses the field whose name was specified.

For arrays, path access is based on (zero-based) array-style indexing. Array indices can be used to retrieve either a single element from an array, or a whole subset of an array. Accessing a single element is achieved by providing a single index argument (zero-based element position), while obtaining a subset of an array is achieved by

providing the start and end (zero-based) index positions; the returned subset is from position start to position

end - 1; the end position argument is optional. If a position argument is negative then the element position is

counted from the end of the array (-1 addresses the last element, -2 next to last, and so on).

Multisets have similar behavior to arrays, except for retrieving arbitrary items as the order of items is not fixed in multisets.

Attempts to access non-existent fields or out-of-bound array elements produce the special value MISSING. Type errors

will be raised for inappropriate use of a path expression, such as applying a field accessor to a numeric value.

The following examples illustrate field access for an object, index-based element access or subset retrieval of an array, and also a composition thereof.

({"name": "MyABCs", "array": [ "a", "b", "c"]}).array (1)

(["a", "b", "c"])[2] (2)

(["a", "b", "c"])[-1] (3)

({"name": "MyABCs", "array": [ "a", "b", "c"]}).array[2] (4)

(["a", "b", "c"])[0:2] (5)

(["a", "b", "c"])[0:] (6)

(["a", "b", "c"])[-2:-1] (7)

| 1 | Returns [["a", "b", "c"]] |

| 2 | Returns ["c"] |

| 3 | Returns ["c"] |

| 4 | Returns ["c"] |

| 5 | Returns [["a", "b"]] |

| 6 | Returns [["a", "b", "c"]] |

| 7 | Returns [["b"]] |

Primary Expressions

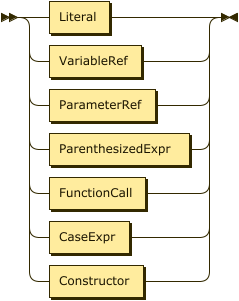

PrimaryExpr

The most basic building block for any expression in SQL++ is Primary Expression. This can be a simple literal (constant) value, a reference to a query variable that is in scope, a parenthesized expression, a function call, or a newly constructed instance of the data model (such as a newly constructed object, array, or multiset of data model instances).

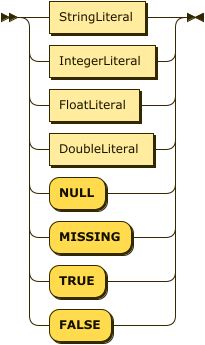

Literals

Literal

The simplest kind of expression is a literal that directly represents a value in JSON format. Here are some examples:

-42 "Hello" true false null

Numeric literals may include a sign and an optional decimal point. They may also be written in exponential notation, like this:

5e2 -4.73E-2

String literals may be enclosed in either single quotes or double quotes. Inside a string literal, the delimiter character for that string must be "escaped" by a backward slash, as in these examples:

"I read \"War and Peace\" today." 'I don\'t believe everything I read.'

The table below shows how to escape characters in SQL++.

| Character Name | Escape Method |

|---|---|

Single Quote |

|

Double Quote |

|

Backslash |

|

Slash |

|

Backspace |

|

Formfeed |

|

Newline |

|

CarriageReturn |

|

EscapeTab |

|

Identifiers and Variable References

Like SQL, SQL++ makes use of a language construct called an identifier. An identifier starts with an alphabetic character or the underscore character _ , and contains only case-sensitive alphabetic characters, numeric digits, or the special characters _ and $. It is also possible for an identifier to include other special characters, or to be the same as a reserved word, by enclosing the identifier in back-ticks (it’s then called a delimited identifier). Identifiers are used in variable names and in certain other places in SQL++ syntax, such as in path expressions, which we’ll discuss soon. Here are some examples of identifiers:

X customer_name `SELECT` `spaces in here` `@&#`

A very simple kind of SQL++ expression is a variable, which is simply an identifier. As in SQL, a variable can be bound to a value, which may be an input dataset, some intermediate result during processing of a query, or the final result of a query. We’ll learn more about variables when we discuss queries.

Note that the SQL++ rules for delimiting strings and identifiers are different from the SQL rules. In SQL, strings are always enclosed in single quotes, and double quotes are used for delimited identifiers.

Parameter References

A parameter reference is an external variable. Its value is provided using the statement execution API.

Parameter references come in two forms, Named Parameter References and Positional Parameter References.

Named parameter references consist of the "$" symbol followed by an identifier or delimited identifier.

Positional parameter references can be either a "$" symbol followed by one or more digits or a "?" symbol. If numbered, positional parameters start at 1. "?" parameters are interpreted as $1 to $N based on the order in which they appear in the statement.

Parameter references may appear as shown in the below examples:

$id $1 ?

An error will be raised in the parameter is not bound at query execution time.

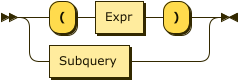

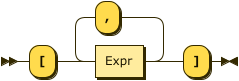

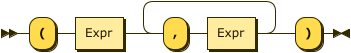

Parenthesized Expressions

ParenthesizedExpr

Subquery

An expression can be parenthesized to control the precedence order or otherwise clarify a query. A subquery (nested selection) may also be enclosed in parentheses. For more on these topics please see their respective sections.

The following expression evaluates to the value 2.

( 1 + 1 )

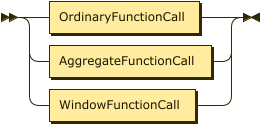

Function Calls

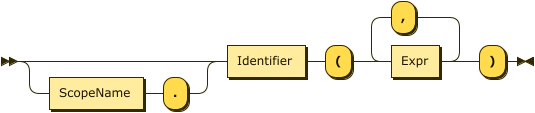

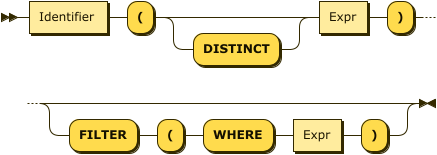

FunctionCall

OrdinaryFunctionCall

AggregateFunctionCall

ScopeName

Functions are included in SQL++, like most languages, as a way to package useful functionality or to componentize complicated or reusable computations. A function call is a legal query expression that represents the value resulting from the evaluation of its body expression with the given parameter bindings; the parameter value bindings can themselves be any expressions in SQL++.

Note that Window functions, and aggregate functions used as window functions, have a more complex syntax. Window function calls are described in the section on Window Queries.

Also note that FILTER expressions can only be specified when calling Aggregation Pseudo-Functions.

The following example is a function call expression whose value is 8.

length('a string')

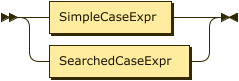

Case Expressions

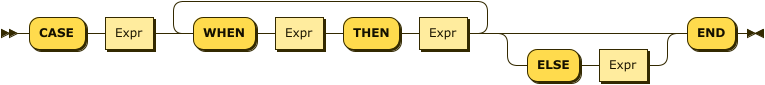

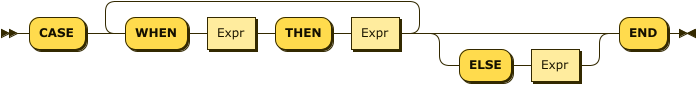

CaseExpr

SimpleCaseExpr

SearchedCaseExpr

In a simple CASE expression, the query evaluator searches for the first WHEN … THEN pair in which the WHEN expression is equal to the expression following CASE and returns the expression following THEN. If none of the WHEN … THEN pairs meet this condition, and an ELSE branch exists, it returns the ELSE expression. Otherwise, NULL is returned.

In a searched CASE expression, the query evaluator searches from left to right until it finds a WHEN expression that is evaluated to TRUE, and then returns its corresponding THEN expression. If no condition is found to be TRUE, and an ELSE branch exists, it returns the ELSE expression. Otherwise, it returns NULL.

The following example illustrates the form of a case expression.

CASE (2 < 3) WHEN true THEN "yes" ELSE "no" END

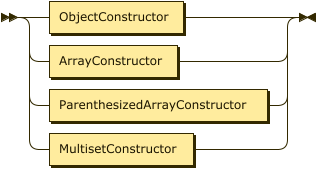

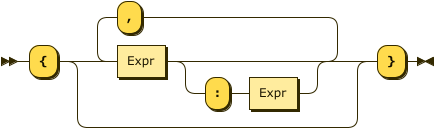

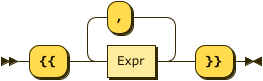

Constructors

Constructor

ObjectConstructor

ArrayConstructor

ParenthesizedArrayConstructor

MultisetConstructor

Structured JSON values can be represented by constructors, as in these examples:

{ "name": "Bill", "age": 42 } (1)

[ 1, 2, "Hello", null ] (2)

| 1 | An object |

| 2 | An array |

In a constructed object, the names of the fields must be strings (either literal strings or computed strings), and an object may not contain any duplicate names. Of course, structured literals can be nested, as in this example:

[ {"name": "Bill",

"address":

{"street": "25 Main St.",

"city": "Cincinnati, OH"

}

},

{"name": "Mary",

"address":

{"street": "107 Market St.",

"city": "St. Louis, MO"

}

}

]

The array items in an array constructor, and the field-names and field-values in an object constructor, may be represented by expressions. For example, suppose that the variables firstname, lastname, salary, and bonus are bound to appropriate values. Then structured values might be constructed by the following expressions:

An object:

{

"name": firstname || " " || lastname,

"income": salary + bonus

}

An array:

["1984", lastname, salary + bonus, null]

If only one expression is specified instead of the field-name/field-value pair in an object constructor then this expression is supposed to provide the field value. The field name is then automatically generated based on the kind of the value expression as in Q2.1:

-

If it is a variable reference expression then the generated field name is the name of that variable.

-

If it is a field access expression then the generated field name is the last identifier in that expression.

-

For all other cases, a compilation error will be raised.

Example

(Q2.1)

FROM customers AS c

WHERE c.custid = "C47"

SELECT VALUE {c.name, c.rating}

This query outputs:

[

{

"name": "S. Logan",

"rating": 625

}

]