Async and Reactive APIs

The Java SDK offers efficient, non-blocking alternatives to the regular blocking API. This page outlines the different options with their drawbacks and benefits.

Reactive Programming with Reactor

You want to consider an asynchronous, reactive API if the blocking API does not suit your needs anymore. There are plenty of reasons why this might be the case, like more effective resource utilization, non-blocking error handling or batching together various operations. We recommend using the reactive API over the CompletableFuture counterpart because it provides all the bells and whistles you need to build scalable asynchronous stacks.

Each blocking API provides access to its reactive counterpart through the reactive() accessor methods:

Cluster cluster = Cluster.connect("127.0.0.1", "Administrator", "password");

ReactiveCluster reactiveCluster = cluster.reactive();

Bucket bucket = cluster.bucket("travel-sample");

ReactiveBucket reactiveBucket = bucket.reactive();

Scope scope = bucket.scope("inventory");

ReactiveScope reactiveScope = scope.reactive();

Collection collection = scope.collection("airline");

ReactiveCollection reactiveCollection = collection.reactive();The reactive API uses the Project Reactor library as the underlying implementation, so it exposes its Mono and Flux types accordingly. As a rule of thumb, if the blocking API returns a type T the reactive counterpart returns Mono<T> if one (or no) results is expected or in some cases Flux<T> if there are more than one expected. We highly recommend that you make yourself familar with the reactor documentation to understand its fundamentals and also unlock its full potential.

The following example fetches a document and prints out the GetResult once it has been loaded (or the exception if failed):

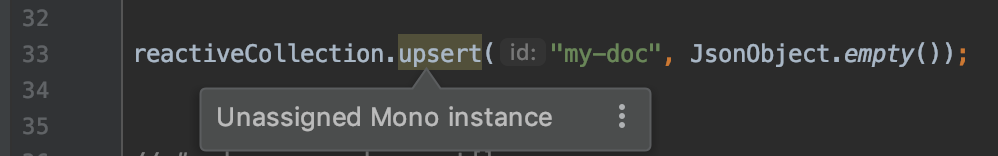

reactiveCollection.get("airline_10").subscribe(System.out::println, System.err::println);It is important to understand that reactive types are lazy, which means that they are only executed when a consumer subscribes to them. So a code like this won’t even be executed at all:

reactiveCollection.upsert("airline_10", JsonObject.create());Modern IDEs like IntelliJ even warn you about that:

You will come across the Flux type in APIs like query where there is one or more row expected.

reactiveCluster.query("select * from `travel-sample`.inventory.airline").flux().flatMap(result -> {

Flux<JsonObject> rows = result.rowsAs(JsonObject.class);

return rows;

}).subscribe(row -> {

System.out.println("Found row: " + row);

});The QueryResult itself is wrapped in a Mono, but the class itself carries a Flux<T> of rows where T is a type of choice you can convert it to (in this example we simply convert it into JsonObject). The flatMap operator allows to map the stream or rows into the previous stream of the original result. If you have more question on how this works, check out the documentation here.

Low Level Asynchronous API with CompletableFutures

Both the blocking API and the reactive one are built on a lower level foundation using the CompletableFuture type. It is built into the JDK starting from version 1.8 and while it is not as powerful as its reactive counterpart it does provide even better performance. In simplified terms, the core-io layer is responsible for mapping a Request to a CompletableFuture<Response>. The blocking API waits until the future completes on the caller thread while the reactive API wraps it into a Mono.

You can access this API by using the async() accessor methods both on the blocking and reactive counterparts:

AsyncCluster asyncCluster = cluster.async();

AsyncBucket asyncBucket = bucket.async();

AsyncCollection asyncCollection = collection.async();We recommend using this API only if you are either writing integration code for higher level concurrency mechanisms or you really need the last drop of performance. In all other cases, the blocking API (for simplicity) or the reactive API (for richness in operators) is likely the better choice.

Batching

The SDK itself does not provide explicit APIs for batching, because using the reactive mechanisms it allows you to build batching code applied to your use case much better than a generic implementation could in the first place.

While it can be done with the async API as well, we recommend using the reactive API so you can use async retry and fallback mechanisms that are supplied out of the box. The most simplistic bulk fetch (without error handling or anything) looks like this:

List<String> docsToFetch = Arrays.asList("airline_10123", "airline_10226", "airline_10642");

List<GetResult> results = Flux.fromIterable(docsToFetch).flatMap(reactiveCollection::get).collectList().block();This code grabs a list of keys to fetch and passes them to ReactiveCollection#get(String). Since this is happening asynchronously, the results will return in whatever order they come back from the server cluster. The block() at the end waits until all results have been collected. Of course the blocking part at the end is optional, but it shows that you can mix and match reactive and blocking code to on the one hand benefit from simplicity, but always go one layer below for the more powerful concepts if needed.

While being simple, the code as shown has one big downside: individual errors for each document will fail the whole stream (this is how the Flux semantics are specified). In some cases this might be what you want, but most of the time you either want to ignore individual failures or mark them as failed.

Here is how you can ignore individual errors:

List<String> docsToFetch = Arrays.asList("airline_10748", "airline_10765", "airline_109");

List<GetResult> results = Flux.fromIterable(docsToFetch)

.flatMap(key -> reactiveCollection.get(key).onErrorResume(e -> Mono.empty())).collectList().block();The .onErrorResume(e → Mono.empty())) returns an empty Mono regardless of the error. Since you have the exception in scope, you can also decide based on the actual error if you want to ignore it or propagate/fallback to a different reactive computation.

If you want to separate out failures from completions, one way would be to use side effects. This is not as clean as with pure functional programming but does the job as well. Make sure to use concurrent data structures for proper thread safety:

List<String> docsToFetch = Arrays.asList("airline_112", "airline_1191", "airline_1203");

List<GetResult> successfulResults = Collections.synchronizedList(new ArrayList<>());

Map<String, Throwable> erroredResults = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

Flux.fromIterable(docsToFetch).flatMap(key -> reactiveCollection.get(key).onErrorResume(e -> {

erroredResults.put(key, e);

return Mono.empty();

})).doOnNext(successfulResults::add).last().block();If the result succeeds the side-effect method doOnNext is used to store it into the successfulResults and if the operation fails we are utilizing the same operator as before (onErrorResume) to store it in the erroredResults map — but then also to ignore it for the overall sequence.

Finally, it is also possible to retry individual failures before giving up. The built-in retry mechanisms help with this:

List<String> docsToFetch = Arrays.asList("airline_1316", "airline_13391", "airline_1355");

List<GetResult> results = Flux.fromIterable(docsToFetch)

.flatMap(key -> reactiveCollection.get(key).retryWhen(Retry.backoff(10, Duration.ofMillis(10)))).collectList()

.block();It is recommended to check out the retry and retryBackoff methods for their configuration options and overloads. Of course, all the operators shown here can be combined to achieve exactly the semantics you need. Finally, for even advanced retry policies you can utilize the retry functionality in the reactor-extra package.

Reactive Streams Integration

Reactive Streams is an initiative to provide a standard for asynchronous stream processing with non-blocking back pressure. The reactor library the SDK depends on has out-of-the-box support for this interoperability specification, so with minimal hurdles you can combine it with other reactive libraries. This is especially helpful if your application stack is built on RxJava.

The easiest way you can do this is by including the Reactor Adapter library:

<dependency>

<groupId>io.projectreactor.addons</groupId>

<artifactId>reactor-adapter</artifactId>

<version>3.2.3.RELEASE</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>io.reactivex.rxjava2</groupId>

<artifactId>rxjava</artifactId>

<version>2.1.0</version>

</dependency>Then, you can use the various conversion methods to convert back and forth between the rx and reactor types. The following snippet takes a Mono<GetResult> from the SDK and converts it into the RxJava Single<GetResult> equivalent.

Single<GetResult> rxSingleResult = monoToSingle(reactiveCollection.get("airline_10"));The same strategy can be used to convert to Akka, but if you are working in the scala world we recommend using our first-class Scala SDK directly instead!